-

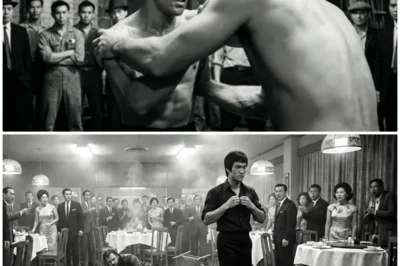

Bruce Lee Was at Restaurant When 250lb Wrestler Said ‘You’re Too Small to Fight’ — 5 Seconds Later

San Francisco, California. The Golden Dragon restaurant. November 8th, 1967. Thursday Night, 9:47 p. m. There were 23 people in…

-

Bruce Lee Was Elevator Fight 4 Men Enclosed Space 1970 — Limited Movement Neutralized All In 2 Min

The doors closed. Four men, one Bruce Lee, space measuring six feet by six feet. Nowhere to run, nowhere to…

-

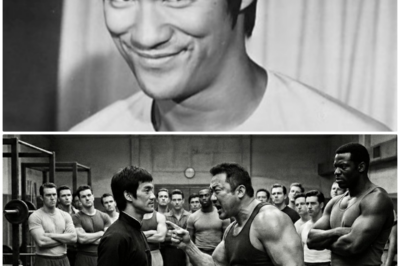

He regretted learning it was Bruce Lee — A 140 Pound Man Made a Giant Beg to Learn

West Hollywood, California. Gold’s Gym on Vine Street. August 3rd, 1971 Tuesday Afternoon, 2:45 p.m. The weights clang against metal….

-

🐘 “Terrified and Sweating: Former Prince Andrew’s Troubling Release from Police Custody!” 💔 “When a royal’s world unravels, the façade can slip away.” Former Prince Andrew’s appearance after being released from police custody has drawn significant attention, with many noting his visibly terrified demeanor. As the fallout from his legal troubles continues, we explore the ramifications for his life and the royal family. Get ready for an in-depth look at the challenges facing this controversial figure! 👇

The Fall of Prince Andrew: A Royal Scandal Unveiled In a world where the glittering facade of royalty often obscures…

-

🐘 “Eric Dane, 53, Passes Away: A Tribute to His Inspiring Fight Against ALS!” ⚡ “When the curtain falls, the legacy of courage remains.” The news of Eric Dane’s death at 53 has sent shockwaves through the entertainment industry, but his brave fight against ALS will not be forgotten. In this heartfelt homage, we explore everything he said about his battle, highlighting the lessons of resilience and hope he imparted to others facing similar struggles. Join us as we honor the memory of a beloved figure in Hollywood! 👇

The Tragic Final Chapter of Eric Dane: A Star’s Battle Against ALS In a world where fame often shields individuals…

-

🐘 “Mamdani’s Tax Proposal Faces Backlash: NYC Councilwoman Calls It ‘Unrealistic’!” ⚖️ “When the cost of governance comes into question, accountability is key!” A New York City councilwoman has publicly criticized Zohran Mamdani’s sweeping tax hike proposal, deeming it unrealistic and potentially harmful to the city’s financial health. As the city navigates this contentious issue, we take a closer look at the implications of her remarks and the reactions from the community. Join us for a thought-provoking analysis of this unfolding political drama! 👇

The Taxation Nightmare: Zohran Mamdani’s Policies Spark Outrage and Fear In the vibrant yet tumultuous landscape of New York City,…

-

🐘 “Sean Hannity’s Take: New Yorkers Face the Consequences of Their Choices!” ⚖️ “When democracy delivers, do voters take ownership?” Sean Hannity’s remarks about New Yorkers getting exactly what they voted for have sparked a wave of discussion about electoral responsibility. As the city navigates challenges, we examine the implications of his statement and how it resonates with residents’ experiences. Join us as we unpack the complexities of voter behavior and political accountability! 👇

The Reckoning of New York: How Zohran Mamdani’s Policies Are Unraveling the City In the bustling streets of New York…

-

🐘 “Zohran Mamdani’s Unaffordable Vision: Are His Policies Too Ambitious?” 🌪️ “When idealism clashes with economic reality, the results can be chaotic!” Zohran Mamdani is facing backlash for advocating policies that critics argue are not only impractical but also beyond the city’s financial reach. As supporters and detractors square off, we analyze the potential consequences of his agenda and the feasibility of his proposed changes. Join us as we unpack the complex dynamics at play in this ongoing political saga! 👇

The Unraveling of Zohran Mamdani: A Mayor’s Absurd Policies Lead to Chaos In the heart of New York City, a…

-

🐘 “Nancy Guthrie’s Home Under Fire: Shocking Findings Spark Google Search Explosion!” 🔥 “In the world of celebrity, secrets rarely stay hidden for long!” The latest buzz surrounding Nancy Guthrie’s home has ignited a massive surge in Google searches, with shocking findings that have left fans and critics alike astounded. As the story unfolds, we take a closer look at what has everyone talking and why this revelation is causing such a stir. Buckle up for a deep dive into the unexpected twists of this unfolding saga! 👇

The Disappearance of Nancy Guthrie: A Shocking Mystery Unfolds In the quiet suburban landscape of Catalina Foothills, Arizona, a chilling…

-

“Julia Roberts’ Heart Wrenching Revelation: ‘Trust is Just a Four-Letter Word!’ 🔥💔😲” In a bombshell confession that has rocked Hollywood, Julia Roberts has shattered her fans’ illusions, stating, “Trust is just a four-letter word!” as she navigates the treacherous waters of heartbreak and betrayal. Once the darling of the silver screen, Julia now finds herself embroiled in a scandal that threatens to tarnish her legacy. Insiders reveal that her marriage is hanging by a thread, with whispers of deception echoing through the halls of Tinseltown. What shocking truths lie ahead for the beloved actress? Prepare for a rollercoaster of emotions as this gripping saga unfolds! 👇

The Shattered Illusion of Julia Roberts In the glimmering world of Hollywood, where dreams are woven with threads of ambition…

-

🐘 “Emotional Insights: Eric Dane’s ALS Fight Captured in Videos Before His Passing!” 🕊️ “When vulnerability meets strength, it creates a powerful narrative!” In a heartbreaking turn of events, Eric Dane’s videos documenting his battle with ALS have come to light, revealing the personal struggles he endured before his death. As fans and loved ones reflect on his journey, these intimate glimpses into his life remind us of the importance of compassion and understanding in the face of illness. Join us as we celebrate the resilience of a man who touched so many lives! 👇

The Heartbreaking Struggle of Eric Dane: A Star’s Final Battle Against ALS In the glitzy realm of Hollywood, where fame…

-

🐘 “Controversial Choices: Mamdani’s $127 Billion NYC Budget and Its DEI Agenda!” 📊 “When priorities clash, the city takes notice!” Mamdani’s $127 billion budget for New York City has sparked an uproar, largely due to its heavy investment in DEI programs. As the community grapples with this bold financial strategy, we explore the varying perspectives on whether these initiatives will foster genuine progress or create further discord. Buckle up for a riveting analysis of the budget that has everyone talking! 👇

The $127 Billion Shockwave: Mamdani’s Budget and the DEI Controversy In the heart of New York City, a storm is…

-

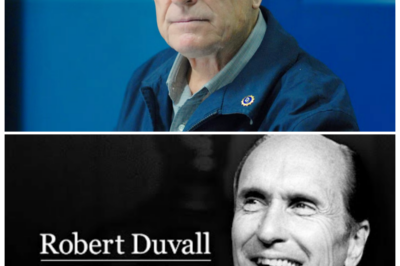

🐘 “Robert Duvall: A Cinematic Journey Through the Life of a Hollywood Legend!” 🎥 “His films are timeless, and his performances are legendary!” In this heartfelt tribute, we celebrate Robert Duvall’s remarkable career and the indelible impact he has had on the film industry. With a career spanning over six decades, Duvall has delivered some of the most iconic performances in cinema history. Get ready to relive the magic as we explore the roles that made him a household name and the stories that shaped his extraordinary life! 👇

The Legacy of Robert Duvall: A Hollywood Giant Falls Silent In the grand theater of life, the curtain has fallen…

-

🐘 “Unveiling the Truth: Mel Gibson and Mark Wahlberg on Oprah’s Surprising Disapproval of ‘Sound of Freedom’!” 📽️ “Every story has multiple sides, and this one is no exception!” Mel Gibson and Mark Wahlberg recently opened up about the unexpected pushback from Oprah Winfrey regarding their film ‘Sound of Freedom.’ As they share their insights into this contentious issue, the conversation raises important questions about the role of power and influence in Hollywood. Get ready for a thought-provoking look at the forces at play in the making of this impactful film! 👇

The Shocking Truth Behind ‘Sound of Freedom’: Mel Gibson and Mark Wahlberg Speak Out In an industry often shrouded in…

-

🐘 “Hollywood’s Dynamic Duo: Billy Bob Thornton and Robert Duvall Share Their Wildest Moments!” 🎉 “Friendship is a journey, and these two have taken us on a wild ride!” In a captivating segment on The Rich Eisen Show, Billy Bob Thornton opened up about his camaraderie with Robert Duvall, sharing stories that highlight the fun and mischief they’ve experienced together. From unforgettable on-set antics to personal escapades, their friendship showcases the magic that can happen when two talented actors unite. Buckle up for a fun-filled exploration of their bond! 👇

The Unbreakable Bond: Billy Bob Thornton Remembers Robert Duvall In the glitzy world of Hollywood, where friendships can often be…

-

🐘 “Stunning Revelation: The Circumstances Surrounding Eric Dane’s Death at 53!” 🔍 “When tragedy strikes, it often brings more questions than answers!” The untimely death of Eric Dane has not only left fans heartbroken but also sparked a wave of speculation about the events leading up to this devastating moment. As we sift through the details and hear from those closest to him, prepare for a deep dive into the life of a man who was much more than just a star—he was a beloved figure whose absence will be felt for years to come! 👇

The Tragic Farewell: Eric Dane Dies at 53 After Battling ALS In a heartbreaking turn of events that has left…

-

🐘 “Men’s Basketball Gold Medal Match Replay: A Battle for Bragging Rights! 🏆” Dive into the action with the full replay of the Men’s Basketball Gold Medal Match, where national pride was on the line! “This is what sports are all about,” fans exclaim. How did the teams rise to the occasion, and what unforgettable moments unfolded? 👇

The Golden Moment: Steph Curry and the Olympic Dream In the realm of sports, few moments shine as brightly as the culmination…

-

🐘 “Kevin Durant Under Fire: How He Made an Already Bad Situation Worse! 💣” In a moment that has shocked fans, Kevin Durant’s latest comments have only intensified the criticism against him. “He needs to reassess his approach,” many are saying, as the drama unfolds. What specific actions have drawn ire, and what steps might he take to mend the situation? 👇

The Downfall of Kevin Durant: A Tale of Burners and Betrayal In the glamorous yet treacherous world of professional basketball, few…

-

🐘 “The NFL is Spiraling Out of Control: A League in Crisis! 😱” As controversies and scandals continue to mount, the NFL finds itself in a precarious position, with fans and analysts alike expressing concern. “This is not just a game anymore; it’s a full-blown crisis,” experts warn. What are the key issues contributing to this downward spiral, and what does it mean for the future of the league? 👇

The NFL’s Chaotic Spiral: A Deep Dive into the Madness In the high-octane world of the NFL, where glory and…

-

🐘 “Mario Barrios and Ryan Garcia: The FINAL Face Off Before the Big Fight! 💣” In a dramatic final press conference, Mario Barrios and Ryan Garcia faced off, showcasing their determination and intensity. “This is more than just a fight; it’s personal,” they both emphasized. What were the highlights of their exchanges, and how will it influence the fight ahead? 👇

The Showdown: Mario Barrios vs.Ryan Garcia – A Battle Beyond the Ring In the electrifying world of boxing, where the stakes are…