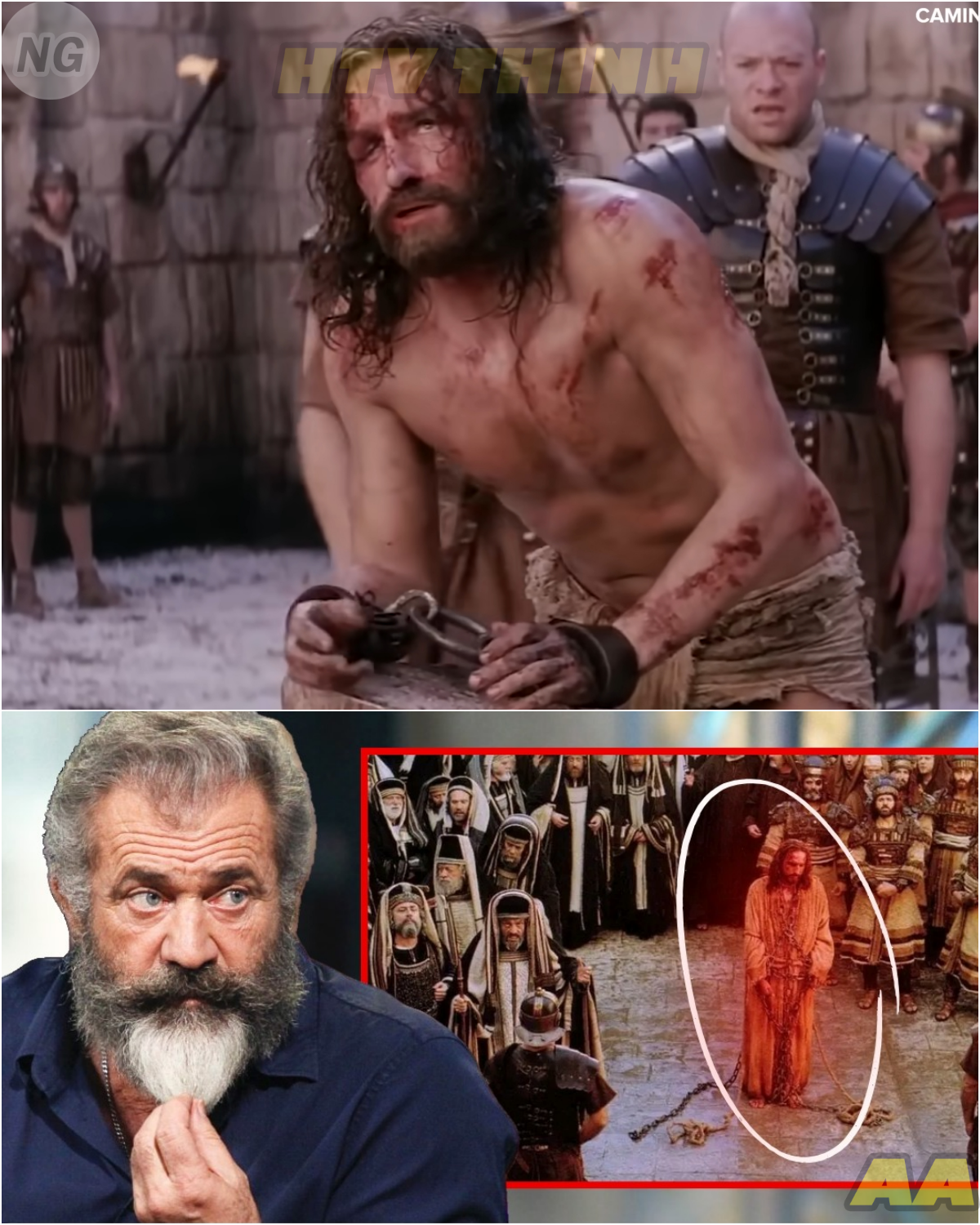

In the annals of modern cinema, few films have generated as much controversy, reverence, and persistent mystery as Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ.

Released in 2004, the movie shattered box office expectations, ignited fierce debate, and left a permanent mark on the cultural landscape.

Yet, behind the film’s brutal realism and staggering commercial success lies a story that many have never heard—a story of haunting coincidences, inexplicable events, and a spiritual battle that continues to confound those who experienced it firsthand.

To this day, as Mel Gibson himself admits, “no one can explain it.”

The journey began not as a calculated career move, but as a compulsion.

In the late 1990s, Mel Gibson was at the height of his Hollywood power: international fame, box office hits, and the rare privilege of creative autonomy.

But beneath the surface, Gibson battled addiction, depression, and a profound sense of emptiness.

In the darkness, he found himself on his knees, praying for deliverance.

It was in that crucible of personal crisis that the vision for The Passion of the Christ was born.

Gibson’s obsession was not with making a conventional biblical epic, but with telling the story of Jesus Christ’s final hours in all their raw, unvarnished brutality.

He poured himself into research, scouring scripture, studying historical texts, and even consulting the mystic visions of Anne Catherine Emmerick.

Authenticity was paramount: Jesus would speak Aramaic, the Romans Latin, and every detail would be stripped of Hollywood gloss.

The result would be a film that was as close to the historical and spiritual reality as possible, with nothing to “soften the blow.”

Hollywood, however, wanted nothing to do with it.

Executives balked at the idea of a film spoken entirely in ancient languages, with no stars, no commercial hook, and a narrative that refused to compromise.

Gibson was undeterred.

He funded the project himself—$30 million for production, another $15 million for marketing.

There were no safety nets.

If the film failed, it would be a personal and financial catastrophe.

But for Gibson, this was no longer a business venture; it was a calling.

He cast Jim Caviezel, a devout Catholic actor with a reputation for intensity and humility, in the role of Jesus.

Caviezel accepted immediately, even after Gibson warned him, “You’ll never work in this town again.”

The cast was filled out with relative unknowns, to ensure that audiences saw not actors, but the story itself.

The film would be shot in the ancient town of Matera, Italy, amid rugged landscapes and brutal weather, using real terrain and practical sets—no green screens, no digital trickery.

From the outset, something felt different.

Cast and crew spoke of an atmosphere of reverence and unease.

During rehearsals, people broke down in tears.

Some described a palpable spiritual force on set.

As filming began, the sense of the uncanny only deepened.

The most infamous incidents were the lightning strikes.

During a crucifixion scene on the hill of Golgotha, Jim Caviezel—suspended on the cross—was struck by lightning.

The crew froze in disbelief as the electrical surge threw Caviezel off balance, causing him to bite through his tongue and cheeks.

He would later require two heart surgeries as a result.

Minutes later, lightning struck again, this time hitting assistant director John Mckelini, who had already been struck once before on the same set.

Scientists call it rare.

Those present called it something else entirely—a sign, a warning, or perhaps a supernatural intervention.

But the lightning was only the beginning.

Crew members began whispering about a strange presence on set.

Some felt dizzy, nauseated, or overcome with emotion during the most intense scenes—the scourging, the carrying of the cross, the crucifixion.

Mel Gibson himself, known for his composure, was seen walking off set during these moments, sometimes praying, sometimes weeping.

The weather in Matera, usually mild, became bizarrely unpredictable.

Sunny mornings would give way to black skies and violent winds.

Sandstorms would erupt without warning, tearing through the set, only to vanish as quickly as they appeared.

Equipment was damaged, tents were ripped from the ground, and the cast endured freezing temperatures and dangerous conditions.

Jim Caviezel’s ordeal did not end with the lightning.

During the scourging scene, a whip—carefully designed to miss—caught his back, leaving a 14-inch scar.

While carrying the massive cross, he slipped and dislocated his shoulder.

Some of the screams heard in the film were not acting, but real cries of pain.

Makeup artists struggled to distinguish between artificial bruises and genuine injuries.

Caviezel contracted hypothermia during the crucifixion scenes, shot in cold, stormy weather.

His initials, JC, and his age (30) during filming—matching those of Jesus at the crucifixion—added another layer of eerie coincidence.

Other cast members were affected as well.

Sudden fevers, sleepless nights, and nightmares plagued the set.

Several crew members reportedly confessed sins and sought baptism during filming.

Luca Lionello, a self-proclaimed atheist who played Judas, converted to Christianity after his experience on set.

Many minor actors and crew members have since refused to discuss the production, even decades later, citing discomfort or a sense that the experience was too sacred—or too strange—to revisit.

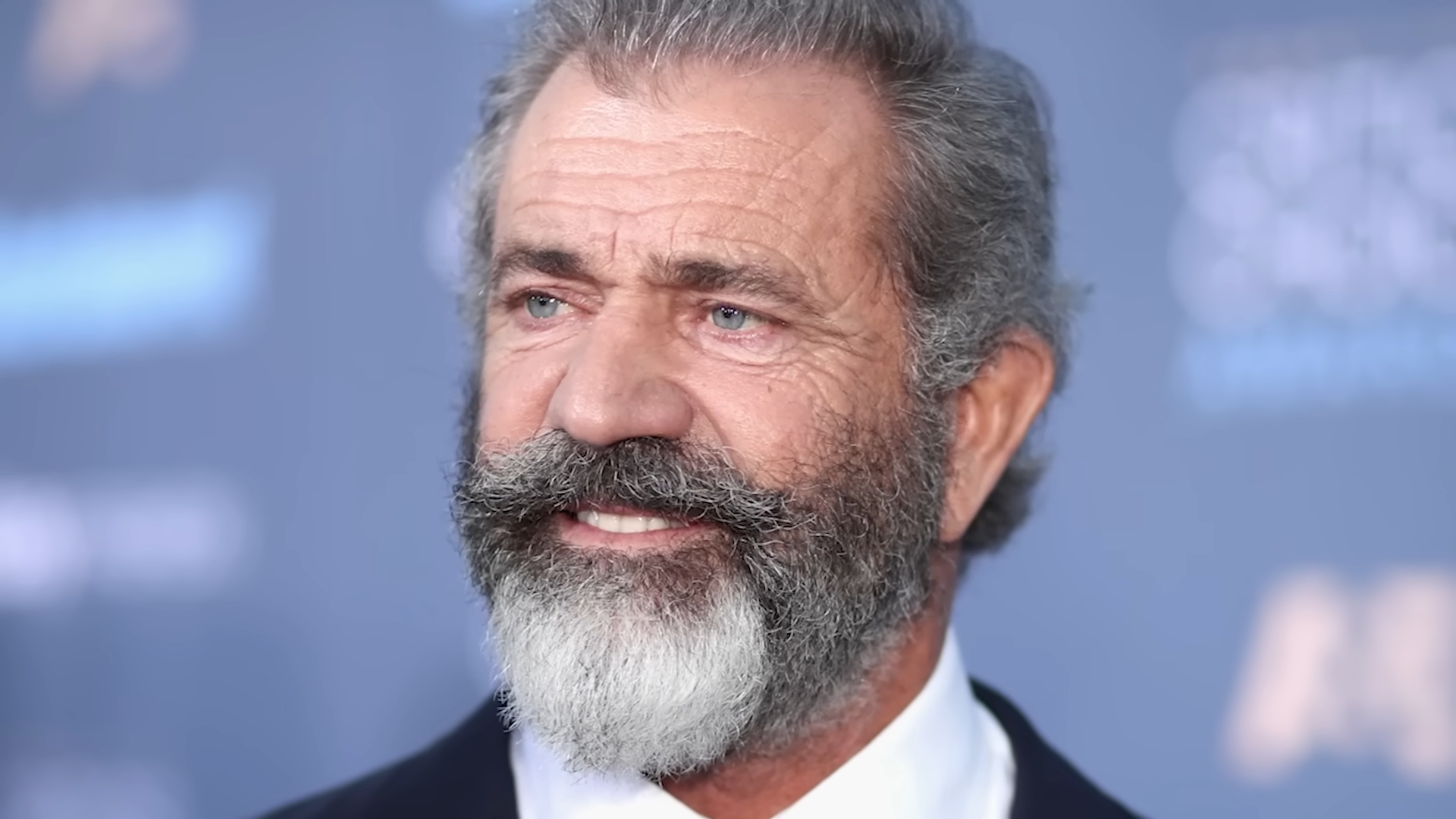

Through it all, Gibson remained mostly silent about the supernatural events.

Those close to him noticed a change: he became more withdrawn, starting each day with prayer and pacing the set with a Bible in hand.

To some, the film set felt like a battlefield—not between actors and critics, but between ancient forces of good and evil.

Gibson would later describe the film as a “spiritual weapon,” and insists that what happened during production was “intense and unexplainable.”

When The Passion of the Christ was finally released on February 25, 2004, it did not arrive quietly.

Hollywood had turned its back on Gibson, critics were poised to attack, and religious leaders were divided.

But the film detonated at the box office, grossing $23.5 million on opening day and $83.8 million by the end of its first weekend—despite being R-rated, subtitled, and filled with graphic violence.

By the end of its run, it had earned $370 million in the U.S.

and over $611 million worldwide, becoming the highest-grossing R-rated film in history at the time.

The success was unprecedented, but so was the backlash.

Jewish organizations, including the Anti-Defamation League, accused the film of promoting anti-Semitic themes.

Critics decried the relentless violence—Roger Ebert called it “the most violent film I have ever seen”—and some accused Gibson of glorifying brutality.

Audiences fainted, wept, or left theaters in shock.

Heated debates erupted on talk shows and in religious circles.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q0lJaS4lpNY

In some countries, the film was embraced with fervor; in others, it faced bans and protests.

Yet, for many Christians, The Passion of the Christ was more than a film—it was a spiritual event.

Churches booked entire theaters, sermons were built around the release date, and viewers reported feeling spiritually transformed, some even claiming physical or emotional healing.

Evangelists used the film as a tool for conversion.

For believers, it became the most powerful evangelistic tool since the Bible itself.

Outside the church, the controversy persisted.

Gibson’s personal life unraveled in the years following the film’s release.

In 2006, he was arrested for driving under the influence and launched into an anti-Semitic rant that shattered his reputation.

More scandals followed: tabloid meltdowns, leaked phone calls, and accusations of inappropriate behavior.

Some saw it as a fall from grace; others, especially those who worked on The Passion, believed the film had changed him in ways that went beyond the natural.

Gibson himself has hinted that the backlash against him was not entirely natural, suggesting that the extraordinary and life-changing nature of the film had consequences.

Despite everything, he remains steadfast in his belief that The Passion was a divine assignment—the work of his life.

In recent years, he has been quietly working on a sequel, though details remain secret.

The legacy of The Passion of the Christ is complex.

It proved that there was a massive, untapped Christian audience that Hollywood had ignored for decades.

Studios rushed to produce faith-based films, but none matched the impact of Gibson’s magnum opus.

For those who lived through the production, the experience was transformative—and, for some, haunting.

Jim Caviezel’s career never recovered; he was quietly blacklisted in Hollywood, but insists he has no regrets, describing the role as a calling.

Many others walked away changed, humbled, or scarred in ways they struggle to articulate.

Perhaps the most enduring mystery is the silence.

Many who worked on the film refuse to speak about it, even now.

Some describe the filming as spiritually intense, overwhelming, or unlike anything they have ever experienced.

Others suggest that what happened on set went beyond art, beyond storytelling, and crossed into the supernatural.

For those who were there, The Passion of the Christ became a spiritual marker—a before and after in their lives.

In the end, The Passion of the Christ was not just a story about Jesus.

For those who made it, it became their own cross to carry.

They saw something.

They felt something.

And they know that what happened behind the scenes cannot be captured in a documentary or recounted in an interview.

It was personal.

It was sacred.

And, in some strange way, it may still be unfolding.

To this day, as Mel Gibson himself acknowledges, “no one can explain it.”

And perhaps that, more than anything, is the true legacy of The Passion of the Christ—a film that was never just a film, but a mystery that continues to haunt, inspire, and challenge all who encounter its story.

News

😱 JD Vance Breaks Down in Tears and Resigns LIVE on TV – Wife’s Explosive Reaction Goes Viral! 🔥📺

On a recent evening that began like countless others in the world of American politics, millions of viewers tuned in…

🚀 Tesla Cybertruck Official Version Stuns with Floating Mode Demo – Inside the Water Resistance Tests! 🌊⚡

Tesla’s Cybertruck has captured global imagination since its dramatic debut, not only for its radical, angular design but also for…

😍 Messi’s Unexpected Gesture Surprises Fans Stuck in Traffic and Lights Up Inter Miami Academy! 📸⚽

The city of Miami has seen its fair share of celebrities, athletes, and unforgettable moments. But few have captivated the…

😲 Unseen VIRAL Footage Captures MESSI Pausing His Walk to Serve Fans – A Moment of Pure Class! ❤️⚽

In the age of viral videos and social media, moments that once would have gone unnoticed now have the power…

🔥 GOAT Chants Erupt for MESSI as Jamaican Footballer Celebrates Snagging His Jersey vs Cavalier! 🐐⚽

Lionel Messi’s presence on the football pitch has always been a spectacle, but his recent appearance in Jamaica was nothing…

🔥 Lionel Messi: The Football Legend Who’s Captivating Celebrities and Stealing Hearts Worldwide! 💖⚽

Lionel Messi is often called the greatest footballer of all time, and his influence stretches far beyond the pitch. His…

End of content

No more pages to load