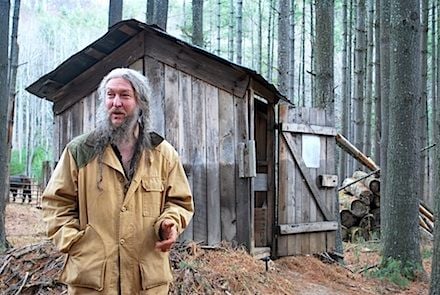

For years, Eustace Conway has loomed large in the public imagination: a rugged frontiersman, a man who walked away from modern life and carved out an existence in the Appalachian wilderness.

Reality-TV viewers watched him on Mountain Men as he built log cabins, tamed mules, and promoted a vision of life rooted in the ancient world.

But now, his family has broken their silence—and what they revealed about his years deep in the woods and at the heart of his self-imposed isolation is far more haunting than anyone anticipated.

From the outside, Conway’s story seemed straightforward.

As a child, he grew up fascinated by nature; by his teens, he was living alone in a tipi and traveling across wildernesses.

In the late 1980s, he purchased land near Boone, North Carolina, and founded Turtle Island Preserve, a 1,000-acre wilderness education center where thousands of students came to learn primitive skills and live off the grid.

He became the archetype of the “last American man” — rugged, independent, unswayed by technology, teaching others to reconnect with nature.

But life is rarely that clean.

Real people rarely live inside neat narratives.

Conway’s family now say the story behind the frontier myth has deep shadows.

In late 2025, with paperwork and interviews in hand, Conway’s extended family sat down for a series of informal talks with a journalist.

They wished to remain mostly anonymous, fearful of rekindling the spotlight, but explained that what they’d witnessed during his time at Turtle Island and in “the wilderness years” revealed a man wrestling with inner demons — not just a peaceful hermit.

According to siblings and cousins, Conway’s choice early on to leave mainstream society had darker underpinnings than mere idealism.

From age 17 when he moved into his tipi, they say the wilderness became less a sanctuary than a shroud.

His correspondence home became sparse; letters stopped when he was deep in the woods.

One sibling recalled: “There were months when we didn’t hear from him at all. No phone, no letter. We assumed he’d just gone down into the back country. Later we realized he wasn’t just gone — he was hiding.”

Doing a 1,000-mile canoe trip, the Appalachian Trail thru-hike, and remote expeditions (all documented) had a cost: detachment from family, from the rhythms of everyday life.

The family say Conway’s singular pursuit of “primitive living” came at the cost of emotional ties and basic social connections.

At Turtle Island, the family describe tensions growing as Conway’s students and interns arrived with idealism and left sharply disillusioned.

They cite long days, blunt discipline, “whiplash” expectations.

One cousin recalled an intern saying: “He told us wilderness is freedom—but it turned out to be a kind of prison.”

The preserve itself came under legal pressure: in 2013 Conway faced building-code violations and pressure from local authorities about the structures on the land, demonstrating that the “back-to-wild” narrative collided with modern regulatory reality.

The family revealed that over the years, Conway had suffered repeated losses: close friends leaving, mentors dying, isolation growing.

They claim that beneath the frontier mantle was a man carrying grief, responsibility for a land he built, and anxiety about legacy.

One niece described visiting and seeing him “standing by the creek at dawn, silent, eyes hollow, listening to the forest as if waiting for something to answer him.”

His decision to broadcast his life on TV (Mountain Men premiered in 2012) seemed to them a plea: not for fame, but for connection.

But it also betrayed the tension between his real life and the image the world expected.

What the family is now revealing goes beyond the known facts: Conway’s break from society was not only philosophical — it was urgent.

According to family records, he felt trapped in his suburban youth, suffocated by the expectations of modern life.

His father, a chemical-engineering professor, encouraged outdoor adventure, but Conway’s thirst was for something more total.

He once told a friend: “It’s not just leaving the city. It’s leaving the pattern.”

He aimed to create a life where every tool was handcrafted, every meal hunted or harvested, every structure built by his own hands.

But pursuing such purity meant cutting ties.

And when a human being rejects the world deeply, sometimes the world rejects them in turn.

By the late 1990s, Turtle Island had become both a sanctuary and a burden.

Land taxes, upkeep, interns, regulatory code — all visible in the public record.

Within the family’s account, this duality wore on Conway.

He felt the wilderness world encroached by modern obligations: phone lines, tax bills, media cameras.

They say he became consumed with proving the authenticity of his life, to such a degree that he began to treat his students not as apprentices but as test-subjects, pushes over boundaries.

One former student told the niece that an exercise that was meant to teach endurance became “a test of loyalty.”

What the public didn’t know: in 2005, Conway’s longtime friend and partner, Preston Roberts (who died in 2018 of liver cancer) was more than an ally—he was one of the few people Conway trusted.

The family say that Preston’s illness and death hit Conway harder than shown on TV.

They say the loss deepened Conway’s sense of isolation and made him question whether the wilderness promise carried the cost of human connection.

In the last decade, Conway has begun reassessing his path.

The family say he’s softened his discipline, sought deeper relationships, and acknowledged that the frontier myth is incomplete without community.

He has spoken about wanting children, building homes, even schooling at Turtle Island.

The 2009 interview noted his partner of 3+ years.

Family members say this change came slowly, after years of confronting loneliness.

For fans of Mountain Men or anyone enchanted by wild living, this revelation complicates the picture.

It shows that living “like the old pioneers” is not a romantic escape—it is a path that demands not only physical endurance but emotional readiness.

Conway’s saga becomes a cautionary tale: independence is admirable, but isolation can be destructive.

It also illuminates a broader cultural myth: the American frontier image as pure freedom vs. modern society as pure bondage.

Conway’s story shows neither is wholly true.

The wilderness offers clarity, but also mirrors one’s deepest vulnerabilities.

Now in his early 60s, Eustace Conway continues at Turtle Island; but the family say his mission has matured.

He is less driven to prove a myth, more focused on connection, legacy, sustainability.

He still hunts, builds log cabins, teaches, but he also heals. He invites, includes, listens.

The wilderness is no longer just his alone—it is shared.

The family reveal: the greatest lesson he hopes to teach isn’t how to build a tipi or start a fire—it’s how to belong, even while being different.

What happens deep in the wilderness doesn’t stay there.

It echoes back into the world. For Eustace Conway, the years he spent in forests, rivers, mountains built a legend.

But what his family now reveal is the man behind it: fragile, brilliant, demanding of both land and people, and ultimately human.

News

🐻 50 Kung Fu Stars ★ Then and Now in 2025

From lightning-fast kicks to gravity-defying flips, the Kung Fu stars of the past defined generations of action cinema. They were…

🐻 Before He Dies, Apollo Astronaut Charles Duke Admits What He Saw on the Moon

At 89 years old, Apollo astronaut Charles Duke has decided it’s time to tell the story he’s kept to himself…

🐻 He Vanished Into the Swamp in 1999 — 25 Years Later, What They Found Left Everyone Stunned

It began on a misty morning in 1999, in the remote wetlands of the northern United States. An experienced hunter…

🐻 Florida Released Hundreds of Robotic Rabbits to Kill Pythons – What Happened Next Shocked Everyone

Officials estimate that pythons have killed 95% of small mammals as well as thousands of birds in Everglades National Park….

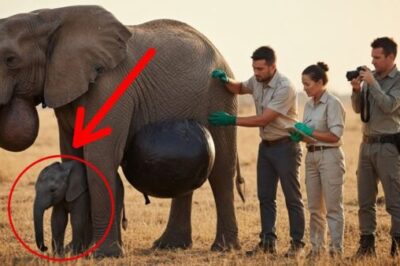

🐻 Baby Elephant Begs Humans to Save Her Mom – and What Happened Next Silenced the Entire Rescue Team

In one of the most heart-wrenching wildlife rescues ever witnessed, a baby elephant was seen desperately pleading for her mother’s…

🐻 She Vanished Before Her Big Debut — But for 20 Years, She Was Hidden in Plain Sight

New York City, 2000. The lights of the fashion world burned brighter than ever, and Simone, a 19-year-old rising model,…

End of content

No more pages to load