“12,000-Year-Old Vault Unearthed in Turkey Reveals Secrets That Could Rewrite Human History 🏺🌌”

Deep beneath the windswept plains of southeastern Turkey, in the province of Şanlıurfa, a discovery made on 12 October 2025 has sent shockwaves through the world of archaeology.

A team led by the Turkish Ministry of Culture, in collaboration with the Göbekli Tepe Research Project, opened what they are calling a “vault” buried under millennia of soil and stone — and what they found inside promises to rewrite our understanding of the dawn of civilization.

The site lies near Göbekli Tepe, itself dated to around 9,500 BCE.

But this newly‑opened chamber appears to be even older: radiocarbon analysis of organic matter taken from the sealed roof indicates an age of approximately 12,000 years.

Dr. Ayşe Tekin, chief archaeologist for the expedition, told reporters in Urfa on 14 October: “We did not expect this.

A sealed chamber of this age is unprecedented in this region.

The contents inside challenge everything we thought we knew.”

On the morning of 12 October, the team carefully removed the last of the overburden — dense limestone slabs that until then had lain undisturbed.

Senior excavation director Kemal Yılmaz described the moment vividly: “When the final stone lifted, a cloud of dust rose.

We held our breath.

We shone lights inside and immediately saw carved pillars, painted walls, and what appeared to be storage vessels, untouched for twelve millennia.

” Among the first recovered items: a large ceramic jar filled with grains, two wooden boxes containing shell ornaments, and a series of chisels made from obsidian and bone.

In a lower chamber, the team uncovered a massive circular stone basin, still holding sediment that when analysed proved to be pollen and plant remains—cultivated cereals such as einkorn wheat, a species thought to have been domesticated later.

Dr.Tekin emphasised: “This suggests cultivation, storage and possibly ritual activity were already underway here 12,000 years ago — decades before current models assume farming took hold.”

One interior wall bore a series of deeply‑carved T‑shaped pillars, similar to those at Göbekli Tepe, but here arranged in concentric rings around the basin.

Among the carvings were depictions of human faces, animals, and geometric symbols.

Archaeologist Dr. Lee Clare commented: “These are not just ritual symbols — they represent architectural planning, social organisation, even writing‑like behaviour far earlier than any tablet we know.

During the press conference, Tekin read an excerpt from the excavation log:

“12 October 2025, 06:45 local—sealed chamber breached.Clear air.

Inner chamber smells of cedar resin.

Echo of footsteps long gone.”

The log stirred imaginations.Cedar resin suggested ritual preservation; footsteps implied human presence inside, maybe even habitation, rather than mere storage.

When asked what it meant, Yılmaz paused.

“It means the people who built this place were not simple hunter‑gatherers, as we thought.

They were organised, they crafted architecture, they preserved seed and ritual.

This vault may have been a sanctuary, a treasury or a time‑capsule.

And until now, it was sealed—intentionally.”

The implications are vast.

For decades, scholars believed large‑scale construction, grain storage and ritual monuments appeared in Mesopotamia around 8,000–7,000 BCE, following agriculture.

But this chamber predates that by more than a thousand years and suggests these processes started earlier.

“Civilisation? Maybe its roots go deeper,” said Clare.

The team is currently analysing the contents.

Among the unique finds: a small carved figurine of a bird perched on a human head, sealed inside a stone box; a bundle of flax fibres bound in a reed mat; and micro‑traces of pigment painted on the chamber walls — deep crimson, indigo and gold.

These colours hint at symbolic or ceremonial practices.

While standard radiocarbon dating confirmed the approximate age, isotopic analysis of grain seeds indicates they were grown locally, in an environment thought to be semi‑arid tundra at the time.

Local heritage officials have begun outreach to local communities.

Elder Fatma Akman of the nearby village told the team: “My grandmother told of footsteps under this hill long ago, a whisper on the wind.

We thought it was story.

Now we see the stones remember.

” The relationship between modern indigenous knowledge and these ancient remains adds emotional weight to the find.

Already, the “vault” is being compared to a time capsule: sealed, intentionally hidden, and designed to preserve something critical.

Scholars speculate it may have been built in response to a climatic event — perhaps the sudden cooling around 10,800 BCE known as the Younger Dryas.

One hypothesis: the chamber stored seed and ritual objects in case of crisis, then sealed and forgotten.

As excavation continues, researchers caution the public: for now, the site remains fragile and off‑limits.

Tekin said: “We are unsealing history itself.

Every step must be careful.

” Over the next year the team will mount high‑definition scans, DNA analysis of plant remains, and 3D modelling of the architecture.

In summary, the unsealing of this 12,000‑year‑old vault beneath Turkey’s ancient hills may mark the earliest known human attempt at preserving culture, seeds and symbols in a built monument.

If proven, it will warp the timeline of civilisation — moving the dawn of organised ritual and storage further back in time than ever thought possible.

Dr. Tekin concluded: “We opened a door to a world long silent.

What we walk into will change how we see ourselves — our past, and perhaps our future.”

News

“Scientists Just Unsealed a 12,000‑Year‑Old Vault in Turkey — What’s Inside Changes History Forever”

“12,000-Year-Old Vault Unearthed in Turkey Reveals Secrets That Could Rewrite Human History 🏺🌌” Deep beneath the windswept plains of southeastern…

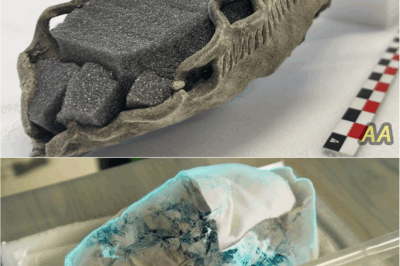

“1,500-Year-Old Moccasin Frozen in Ice Reveals Shocking Secrets That Left Archaeologists Stunned ❄️🥿”**

“Archaeologists Unearth a 1,500-Year-Old Moccasin Frozen in Ice — and What They Found Inside Left Them Stunned ❄️🥿” In the…

“Archaeologists Uncover a 1,500‑Year‑Old Moccasin Frozen in Ice… and What They Found Inside Made Them Pale”

“Archaeologists Unearth a 1,500-Year-Old Moccasin Frozen in Ice — and What They Found Inside Left Them Stunned ❄️🥿” In the…

**“NASA Detects Interstellar Object 3I/ATLAS Suddenly Stop in Space — And the Signal It Sent Moments Later Changed Everything 👁️🛰️”**

“NASA Confirms: Interstellar Object 3I/ATLAS Has Mysteriously Stopped — And What They Detected Next Left Scientists Speechless 🛰️🌌” On the…

“Probe Alert: 3I/ATLAS Suddenly Stops—And What Happens Next Terrifies NASA!”

“NASA Confirms: Interstellar Object 3I/ATLAS Has Mysteriously Stopped — And What They Detected Next Left Scientists Speechless 🛰️🌌” On the…

**“In 2025, Archaeologists Uncovered a Hidden Chamber Beneath Machu Picchu — And What They Found Could Rewrite Human History 🌘”**

“The 2025 Discovery Beneath Machu Picchu That Shattered Everything We Thought We Knew About the Inca Empire 🌘” In June…

End of content

No more pages to load