The Sullivan Mansion was not a home; it was a mausoleum.

Eliza, a freelance graphic designer who lived in a 500-square-foot apartment in Brooklyn, had inherited it. The house, a rotting Gilded Age behemoth in upstate Massachusetts, had been in her mother’s estranged family for generations. Now, it was hers. And she, the last of the Sullivan line, was here to perform the final rites: liquidate.

Her first week was a blur of dust motes dancing in weak autumn light. The house smelled of paper decay, old varnish, and a faint, sharp tang of ozone, as if a storm was perpetually brewing in the attic. She was practical. She wore a KN95 mask, cargo pants, and steel-toed boots. Her job was to separate the antiques (for auction) from the junk (for a dumpster). It was a simple, binary task.

The house, however, was not simple. It was filled with the oppressive weight of a hundred and fifty years of things. Furniture draped in yellowed shrouds, stacks of brittle books, and portraits. So many portraits. Stern, bearded men and pale women in high-collared dresses, all staring at her, the interloper in her neon-orange beanie, with uniform disapproval.

“I get it,” she muttered to a particularly grim-looking ancestor, “you don’t like my tattoos. The feeling is mutual.”

She was working in the third-floor library, a room that had been sealed since the 1950s. The air was dead. On a mahogany desk, beneath a fossilized copy of The Saturday Evening Post, she found a thick, leather-bound portfolio. It was heavy, embossed with a simple, “Ashford & Sons Photography, Boston.”

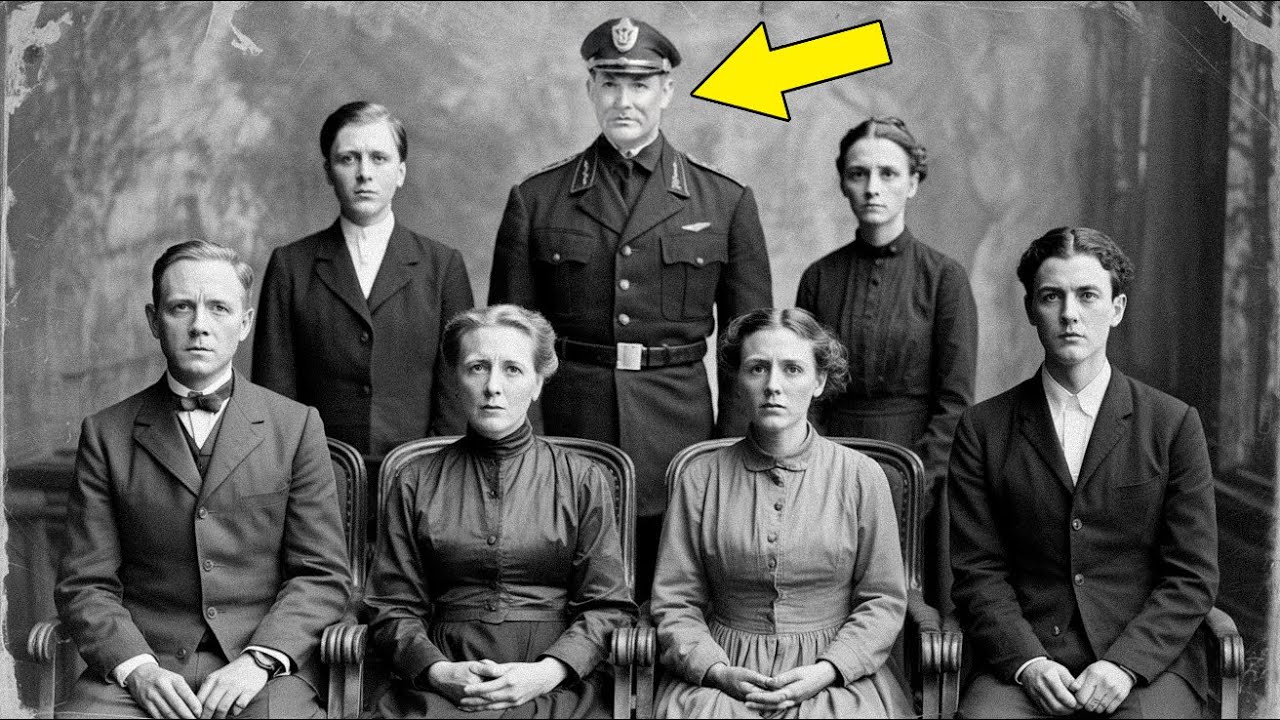

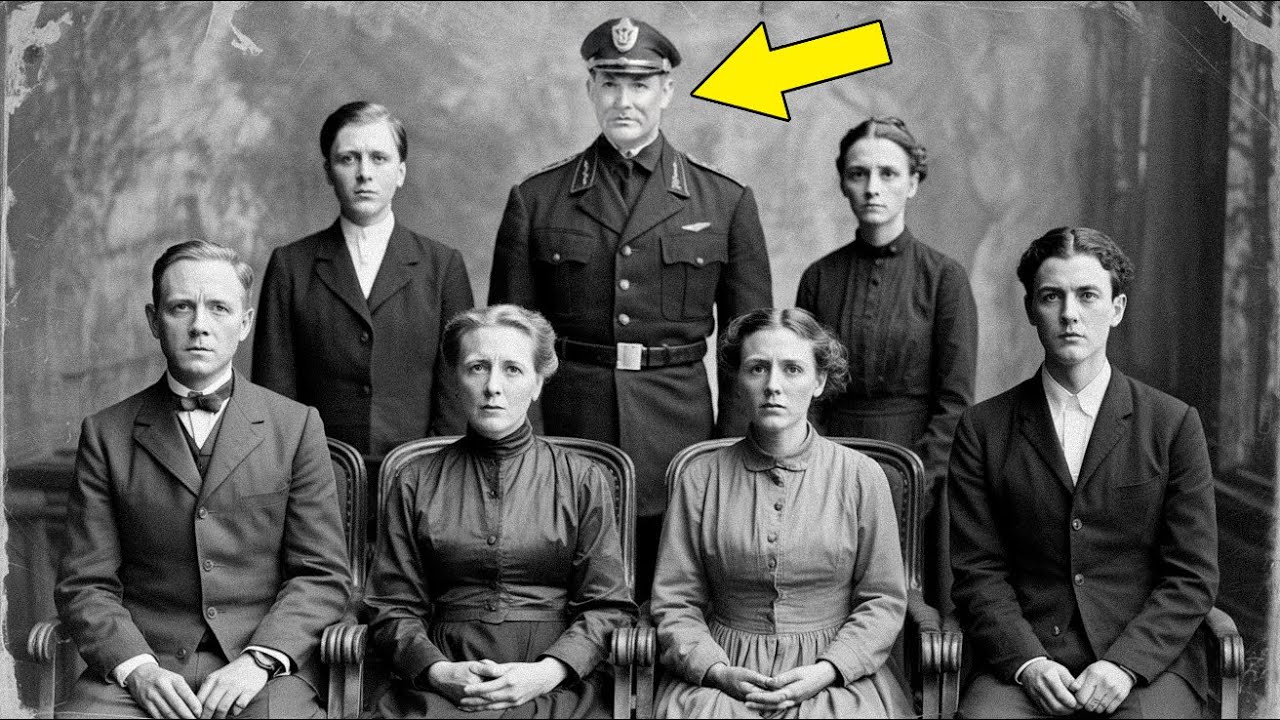

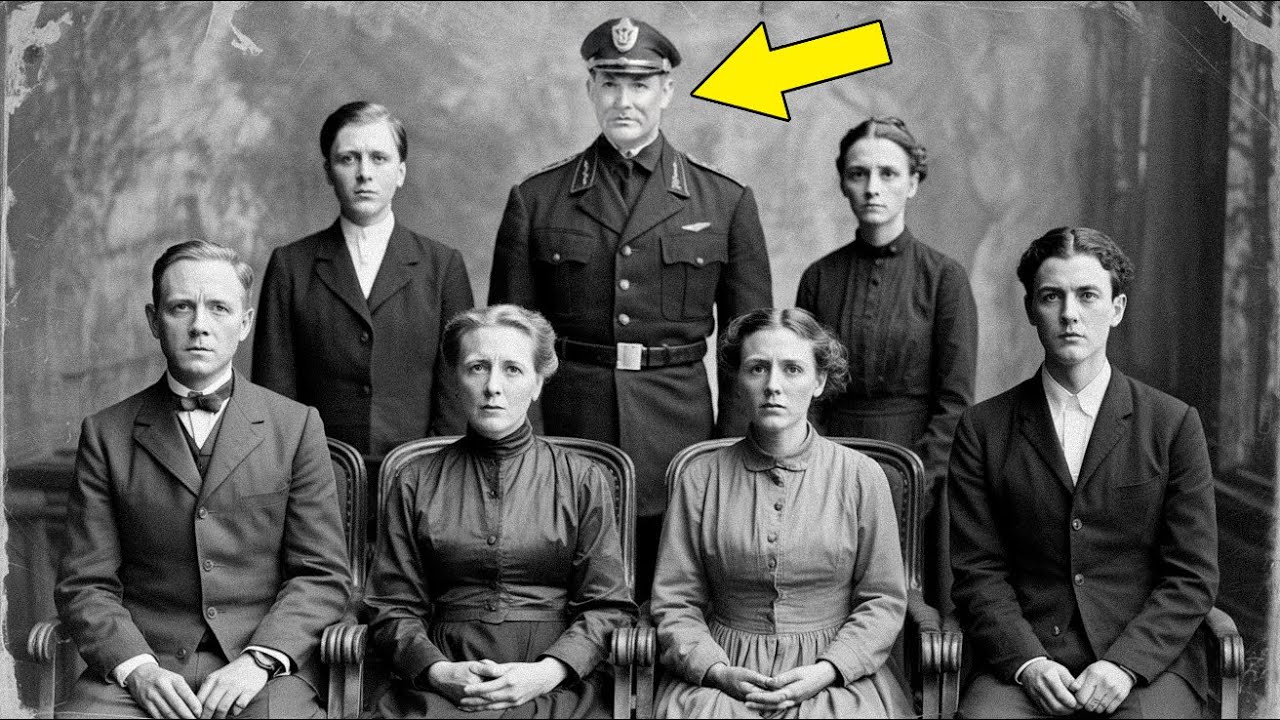

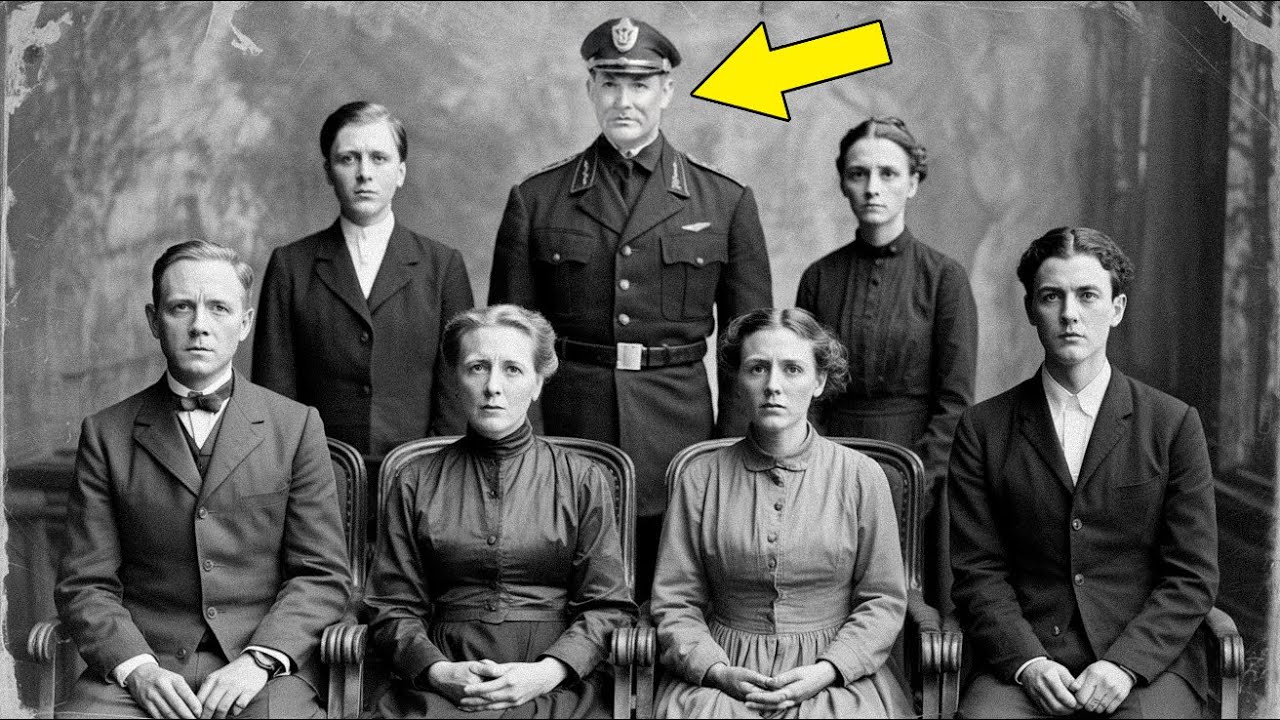

Inside, nestled in water-stained silk, were glass plate negatives and their corresponding prints. Most were what she expected: stiff family groupings, a boring landscape, a dead child in a christening gown. Standard Victorian creepiness. She was about to add the portfolio to the “junk” pile when one image stopped her cold.

It was the one dated 1887.

The “normalcy” of it was what felt so wrong. It was the quintessential Sullivan family portrait. The elderly couple, Robert and Margaret, seated in the center. Three adults and two teenagers standing behind. Their faces were formal, bored, constrained by the long exposure time.

But it was the seventh figure, the one on the far left, that held her.

He was a soldier, standing slightly apart from the family. He wore the high-collared U.S. Army uniform of the 1880s. He was handsome, but his face was a mask of tension. His gaze was directed downward, toward the seated couple, but it was his eyes…

Eliza, a visual professional, was drawn to the technical details. She pulled a small digital loupe from her pocket, a tool she used for checking print registration. She clicked on its tiny LED and placed it over the soldier’s face.

The print quality was astonishing. The albumen paper had yellowed, but the detail was sharper than any digital file. She could see the texture of his wool uniform, the individual hairs of his mustache. She moved the loupe to his left eye.

And she screamed. A dry, choked sound that was instantly smothered by the room’s thick dust.

There was a face.

It wasn’t a reflection of the photographer. It wasn’t a smudge or a chemical flaw. Inside the dark, perfectly rendered pupil of the soldier, clear as day, was a second face. A woman’s face. Her mouth was open, her features sharp and angular, her expression a perfect, silent rictus of terror.

Eliza dropped the loupe. Her heart was a cold hammer against her ribs. This wasn’t possible.

She backed away, her rational mind scrambling for purchase. It was “pareidolia,” the psychological quirk of seeing faces in random patterns. A water stain. A trick of the light.

She forced herself to pick up the loupe and look again.

The face remained. It was not a pattern. It was a person. It was, she realized with a fresh wave of nausea, integrated into the original image. The light and shadow on the screaming woman’s face were consistent with the light in the studio. It was as if, at the moment of exposure, this tiny, screaming woman had been there, in his eye.

The photograph, which seconds ago had been a piece of junk, now felt like a curse. This was the “strange detail” that fractured her practical world. The Sullivan Mansion wasn’t just a mausoleum of things; it was a mausoleum of secrets. And she had just found the key.

She did not sleep that night. She moved to a hotel in town, the photograph clutched in a protective archival box. The house, with its staring portraits and dead air, was suddenly, viscerally, unbearable.

In the sterile, beige-and-blue anonymity of the ‘Heritage Inn,’ Eliza opened her laptop. Her pragmatism had returned, but it was now weaponized. She was no longer an heir liquidating assets; she was a researcher hunting a ghost.

Her search terms were simple: “Ashford & Sons Photography 1887,” “Sullivan Family 1887,” “US Army Boston 1880s.”

The internet, as it always does, provided.

The first hits were boring. Genealogical records, society pages. The Sullivans were wealthy. They threw parties. Then, a digitized academic journal from 2019, written by a Dr. Sarah Chen. The title hit her like a physical blow: “Anomalies in 19th Century Portraiture: The Sullivan Photograph of 1887.”

Eliza read, her blood turning to ice water. Dr. Chen had found the same photo, or a copy of it, in a university archive. She had subjected it to every test imaginable. The conclusion was the same. The face was “integrated into the original exposure.” It was “a technical and physical impossibility.”

But Dr. Chen had gone further. She had identified the soldier. Colonel James Whitmore.

And she had, with chilling academic precision, cross-referenced the date of the photograph with local Boston newspapers.

Eliza clicked the link to a digitized newspaper clipping. Page 3, The Boston Globe, October 19th, 1887.

“MISSING PERSON. Miss Eleonora Margaret Hayes, 18 years of age, absent from her residence since the evening of October 18th… last seen at a social gathering at the Sullivan residence…”

Eliza’s breath hitched. At the Sullivan residence.

She dug deeper, falling down a rabbit hole of historical pain. Eleonora Hayes, a musician, a doctor’s daughter. She was at a piano recital at the Sullivan mansion. She finished her piece, a Chopin nocturne, and went to the music room to rest. She was never seen again.

The investigation was cursory. The police assumed she had eloped. But her family’s private letters, now digitized, told a different story. Eleonora’s own diary, a faint, spidery script, mentioned “uncomfortable attentions” from a “Colonel W.”

Colonel James Whitmore. He was at the party. He was a “family friend” of the Sullivans. Police records, sparse as they were, noted he was “observed leaving the Sullivan residence through the garden entrance approximately 45 minutes after Miss Hayes’s performance concluded.”

Eliza felt a profound, suffocating darkness. The screaming face in the soldier’s eye. A missing girl. A party in that house.

This wasn’t a ghost story. It was a murder investigation, 130 years too late.

She found the other threads of the story, the ones that defied all rational explanation. The photographer, Charles Ashford, had not died of “nervous exhaustion” as his obituary claimed. A descendant, a “Dr. Thomas Ashford,” had shared the man’s private journal.

Eliza read the entry, dated October 19th, 1887, the day after the photo session.

“I have seen the devil’s work. It is not a double exposure. I checked the plates. The glass is clean. But in the development bath, it appeared. I saw it swim into view. The girl in his eye. I printed it, thinking it a flaw. It is not a flaw. It is a witness. I will carry this mystery to my grave. And the grave will not release me from it.”

Ashford had closed his studio days later. He died a year after that, in an asylum.

But it was the last piece of the puzzle, the one that made Eliza’s skin crawl, that she found in a forgotten genealogical forum. A descendant of the Whitmore family, trying to clear the Colonel’s name, had posted—and then quickly deleted—a scan of a private, undated note found in the Colonel’s effects.

The forum’s cache had saved it.

“The girl has not released me. Every October 18th, I see her eyes at midnight. She is in the room. She is always screaming. She will not let me go.”

A final search: “Colonel James Whitmore, death.”

He died on October 18th, 1921. A “catastrophic stroke.” The coroner noted the time of death: “approximately midnight.”

A cold, logical dread settled over Eliza. This was a pattern. A cycle. A curse.

She looked at her phone. The date was displayed in a clean, sans-serif font.

October 17th.

She was supposed to meet the auctioneer at the house tomorrow morning. October 18th. She had to go back.

The drive back to the mansion was different. The autumn trees, which before had been a blaze of glorious color, now looked like skeletal, grasping hands. The house, when it came into view, did not look like a relic. It looked like a predator, waiting.

She walked in. The air was no longer dead. It was buzzing. It was the same feeling she got right before a migraine, a low-level electrical hum that set her teeth on edge. The smell of ozone was stronger.

“This is stupid, Eliza,” she whispered to herself. “You’re spooked. It’s an old house. It’s an old story.”

But she clutched the archival box containing the photograph like a talisman.

She spent the day working, pointedly, practically. She labeled furniture with green painter’s tape. She cataloged silver. She was a professional. She was in control.

The sun began to set. The weak light fled the house, and the shadows pooled in the corners like spilled ink. The temperature dropped, not by a few degrees, but by twenty. She could see her breath.

And she heard it.

A single, perfect piano key, struck in the distance. A high C.

It came from the second floor. The music room.

Eliza’s heart stopped, then restarted with a painful, suffocating kick. “Hello?” Her voice was a thin thread.

The single note was followed by another. And another. A slow, stumbling, out-of-tune melody. A child practicing. Or someone who could barely remember how to play.

A Chopin nocturne.

Eliza was backing toward the door, fumbling for her keys, when the grand foyer light—a three-tiered crystal chandelier—flickered and went out. She was plunged into a cold, absolute darkness, broken only by the pale blue light of her phone’s screen.

The music stopped.

The silence that followed was worse. It was an active, listening silence.

“I’m not scared of you,” she lied, her voice shaking. “I know what you did.”

A floorboard creaked above her. In the music room. And then another, in the hallway.

Creak.

Pause.

Creak.

It was descending the main staircase.

Eliza was frozen. She could feel the “fight or flight” response as a chemical burn in her veins, but her feet were lead. She pointed her phone’s flashlight at the base of the grand staircase.

Nothing. Just shadows and dust.

Creak.

It was at the bottom. It was in the foyer with her.

“Who’s there?” she shouted.

“The girl… has not released me,” a voice whispered.

It came from everywhere at once. It was a dry, rasping sound, like dead leaves skittering on pavement. The smell of ozone was suddenly, overwhelmingly, mixed with the smell of damp wool and grave dirt.

“Colonel Whitmore,” Eliza said, the name tasting like ash.

“She will not let me go,” the voice rasped, closer now.

The temperature plummeted. A layer of frost, delicate and impossible, bloomed across the mirror on the wall. Eliza could see her own terrified face, pale and wide-eyed, and behind her…

He was there. Not a man. A shape. A column of darkness that was colder than the room. He wore the high-collared uniform, his features blurred, as if seen through black water.

He was staring at the archival box in her hand.

“You did it,” Eliza whispered, tears of terror freezing on her cheeks. “You killed her. In this house.”

The shape drifted toward her. “She is in the room. She is always screaming.”

“I’m not her!” Eliza screamed, recoiling.

“You brought the mirror,” the voice hissed, and he pointed a shadowy, indistinct hand at the box. “You brought her eye.”

He lunged.

It was not a physical attack. It was a psychic one. A wave of pure, concentrated cold and despair hit her. It was the feeling of being buried alive. It was the feeling of a secret held for a hundred years, a cancer of the soul.

Eliza fell, dropping the box. The photograph slid out, landing face-up on the marble floor.

The Colonel’s shape stopped. He turned. He was looking at the photograph. He was looking at himself.

“It’s not fair,” he whimpered, and the voice was no longer a man’s, but a petulant, terrified boy’s. “I see her eyes. At midnight. She will not let me go.”

And then, Eliza heard it. A new sound. Faint, at the edge of hearing. A high-pitched, thin wail. It was the sound of a kettle, the sound of a scream.

It was coming from the photograph.

The Colonel turned back to Eliza. “You will take it. You will burn it. You will release me.”

He was advancing again. The cold was unbearable. Eliza knew, with a certainty that went beyond logic, that if he touched her, she would join the collection of dusty, forgotten things in this house. She would be just another portrait on the wall.

“No,” Eliza said, her voice shaking but finding a sudden, strange new strength. She was a Sullivan. This was her house.

“She’s not yours to keep,” Eliza shouted, pushing herself to her feet. She grabbed the photograph from the floor.

The effect was instantaneous. The Colonel’s shape recoiled as if she’d struck him.

“I know what you did!” Eliza shouted, holding the photo aloft like a shield. “And you are not welcome here!”

She was screaming now, not in terror, but in rage. “You don’t get to be released! You don’t get to be free! You killed her, and you trapped her! Let her go! ELEONORA!”

She screamed the name.

The house exploded.

It felt like a sonic boom. The windows on the first floor shattered outward. The chandelier, dark for a century, flashed once, a brilliant, blinding white, and then every crystal in it turned to dust. The oppressive cold vanished, replaced by a sudden, rushing warmth.

A wind, born from nowhere, tore through the foyer, slamming every door in the house shut.

The Colonel’s shadow was ripped apart, dissolving like smoke in a gale. His final sound was a shriek of astonishment, of disbelief.

And then, silence.

The only sound was Eliza’s own ragged breathing. The air was clean. The buzzing was gone. The smell of ozone and damp wool was gone, replaced by the simple, clean scent of the night air coming through the broken windows.

She was alone. Truly alone.

Dawn found her sitting on the front steps, wrapped in an antique quilt, sipping lukewarm coffee from a thermos. The house behind her was quiet. It was, for the first time, just a house. The auctioneer was due in an hour.

She had survived. She had… won?

She looked at the thing in her lap. The Sullivan Photograph. It had survived the night, unblemed.

She picked it up. She had to know.

Her hands were steady. She looked at the soldier, Colonel James Whitmore. He was still handsome. He was still rigid. His eyes were still gazing downward.

She lifted the loupe to his left eye.

The pupil was dark. It was clean. It was empty.

The screaming face was gone.

A sob of pure, profound relief escaped her. It was over. Eleonora was free. The Colonel was gone. The curse was broken.

She was about to put the loupe away forever when her gaze drifted. Just a professional’s habit. Checking the rest of the image. The composition. The focus.

Her eye landed on the seated matriarch, Margaret Sullivan. Eliza’s ancestor. The woman who had hosted the party. The one who had, according to the society pages, “led the search” for poor, missing Eleonora.

She was wearing a large, dark brooch at her throat. A piece of jet or onyx, polished to a mirror shine.

Eliza’s blood, which had just begun to warm, turned to slush.

“No,” she whispered. “Please, no.”

Almost against her will, she lifted the loupe one last time. She placed it over the tiny, dark speck on Margaret Sullivan’s dress.

The brooch, in the 1887 photograph, was not just a piece of jewelry. It was a perfect, black mirror. And in its reflection, rendered in impossible, microscopic detail, was a new face.

It was not Eleonora.

It was the face of Colonel James Whitmore. His mouth was open. His features were sharp and angular. He was screaming.

News

The TV Moment That Shattered Barry Gibb — And Revealed the Pain He Tried to Hide

Barry Gibb, the last surviving member of the legendary Bee Gees, is known for his powerful voice and his role…

“Please, Let Me In, I’m Freezing,” Pleaded the Homeless Man — Then Undercover CEO Did This!

The bell above the door chimed, a delicate, silver sound that was immediately swallowed by the expensive, curated silence of…

Guns N’ Roses Doesn’t Want This to Come Out

In a shocking legal twist that could have massive implications for Guns N’ Roses, former manager Allan Nan has filed…

Little Girl Was Kicked Out By Stepfather After Mother Funeral. Suddenly, Millionaire Rushed In And..

In the heart of a small town, a tragic story unfolded that would touch the hearts of many. Little Emily,…

At 81, Gladys Knight Finally Tells the Truth About Michael Jackson

In a rare and deeply emotional moment, Gladys Knight has broken her silence about her relationship with Michael Jackson, revealing…

George Thorogood and Sammy Hagar Rock the Stage with “Move It On Over”

It’s a night that fans will never forget. George Thorogood and Sammy Hagar, two of the biggest names in rock…

End of content

No more pages to load